Shuttle Discovery over Bern, Morat, and Bienne

© Courtesy of NASA with thanks to Claude Nicollier for forwarding the originals to the Space Center EPFL.

On July 28, 2005 while on the STS-114 mission, the United States Space Shuttle Discovery performed a “flip” manoeuver just before docking to the International Space Station (ISS). The main goal was for the astronauts aboard the ISS to take detailed pictures of the Shuttle’s thermal protection system to be able to verify its integrity. At that time, the ISS and the Shuttle were 200 m apart and both moving at approximately 7.6 km/s (27’000 km/hour). This manoeuvre took place just above Switzerland at an altitude of 353 km. There was little to no cloud coverage, which allowed to take these stunning images.

Uyuni salt flat, Bolivia

© contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017), processed by ESA

The image shows part of Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni – the largest salt flat in the world.

Occupying over 10 000 sq km, the vast Salar de Uyuni lies at the southern end of the Altiplano, a high plain of inland drainage in the central Andes. Some 40 000 years ago, this area was part of a giant prehistoric lake that dried out, leaving behind the salt flat.

Salt from the pan has been traditionally harvested by the local Aymara people, who still predominate in the area. But the Uyuni is also one of the richest lithium deposits in the world, at an estimated 9 million tonnes.

The geometric shapes in the upper left are large evaporation ponds of the national lithium plant, where lithium bicarbonate is isolated from salt brine. Lithium is used in the manufacturing of batteries, and the increasing demand has significantly increased its value in recent years – especially for the production of electric-car batteries.

The surrounding terrain is rough in comparison to the vast salt flat. In the lower right we can see the 20 km-wide alluvial fan of the Rio Grande de Lípez delta.

On the whole, the Salar de Uyuni is very flat, with a surface elevation variation of less than 1 m. This makes the area ideal for calibrating satellite radar altimeters – a kind of radar instrument that measures surface topography. ESA’s CryoSat and the Coperncius Sentinel-3 satellites carry radar altimeters.

This image, also featured on the Earth from Space video programme, was captured by the Copernicus Sentinel-2B satellite on 17 May 2017.

Open Day at ESTEC

© ESA – J. Harrod

Claude Nicollier (Mission STS 103)

© NASA

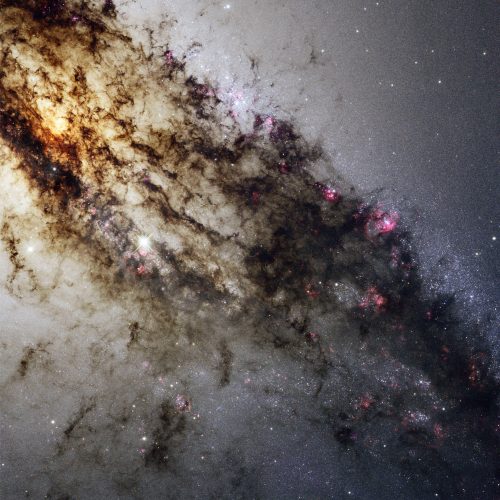

Spectacular Hubble view of Centaurus A

© NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage (STScI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration. Acknowledgment: R. O’Connell (University of Virginia) and the WFC3 Scientific Oversight Committee

Centaurus A, also known as NGC 5128, is well known for its dramatic dusty lanes of dark material. Hubble’s new observations, using its most advanced instrument, the Wide Field Camera 3, are the most detailed ever made of this galaxy. They have been combined here in a multi-wavelength image which reveals never-before-seen detail in the dusty portion of the galaxy.

As well as features in the visible spectrum, this composite shows ultraviolet light, which comes from young stars, and near-infrared light, which lets us glimpse some of the detail otherwise obscured by the dust.

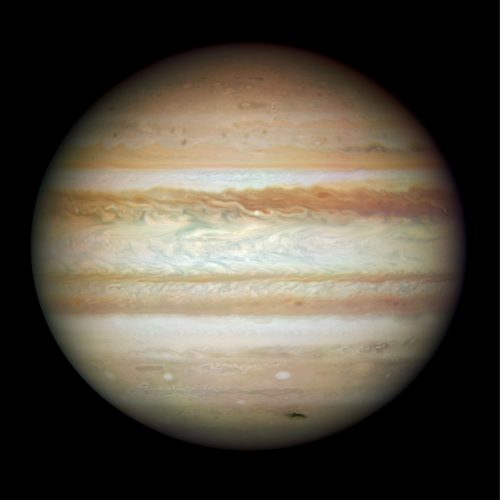

Collision leaves giant Jupiter bruised

© NASA, ESA, Michael Wong (Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, MD), H. B. Hammel (Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO) and the Jupiter Impact Team

This Hubble picture, taken on 23 July, is the first full-disc, natural-colour image of Jupiter made with Hubble’s new camera, the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). It is the sharpest visible-light picture of Jupiter since the New Horizons spacecraft flew by that planet in 2007. Each pixel in this high-resolution image spans about 119 kilometres in Jupiter’s atmosphere. Jupiter was more than 600 million kilometres from Earth when the images were taken.

The dark smudge at bottom right is debris from a comet or asteroid that plunged into Jupiter’s atmosphere and disintegrated.

In addition to the fresh impact, the image reveals a spectacular variety of shapes in the swirling atmosphere of Jupiter. The planet is wrapped in bands of yellow, brown and white clouds. These bands are produced by the atmosphere flowing in different directions at various places. When these opposing flows interact, turbulence appears.

Such data complement the images taken from other telescopes and spacecraft by providing exquisite details of atmospheric phenomena. For example, the image suggests that dark “barges” — tracked by amateur astronomers on a nightly basis — may differ both in form and colour from barge features identified by the Voyager spacecraft. (The Great Red Spot and the smaller Red Oval are both out of view on the other side of the planet.)

This colour image is a composite of three separate colour exposures (red, blue and green) made by WFC3. Additional processing was done to compensate for asynchronous imaging in the colour filters and other effects.

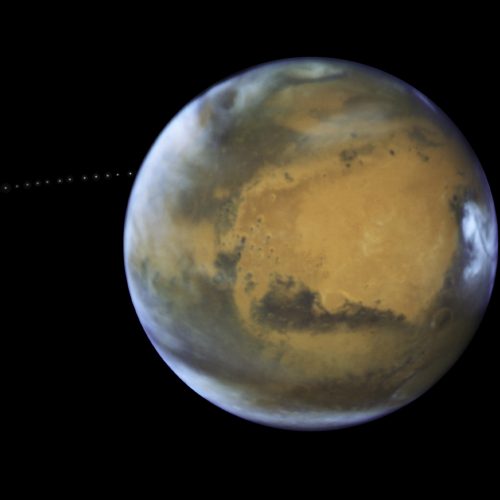

Phobos orbiting Mars

© NASA, ESA and Z. Levay (STScI) Acknowledgment: J. Bell (ASU) and M. Wolff (Space Science Institute)

The sharp eye of the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope captured the tiny moon Phobos during its orbital trek around Mars on 12 May 2016. The observations were intended to photograph Mars while it was on its closest approach to Earth along its orbit, so the moon’s cameo appearance was a bonus.

Over the course of 22 minutes, Hubble took 13 separate exposures, allowing astronomers to create a timelapse video showing the movement of Phobos around its host planet. Because the moon is so small, just 27×22×18 km, it appears star-like in the images.

It also orbits incredibly close to Mars, just 6000 km above the planet, making it closer to its parent planet than any other moon in the Solar System.

Sibling Deimos orbits much further out, at a distance of some 23 500 km.

While the origin of the moons is much debated, their fate is inevitable. Phobos is gradually spiraling in towards Mars and within 50 million years will likely either break up due to the planet’s gravity, or crash into its surface. Meanwhile, the opposite is true for Deimos: its orbit is slowly taking it away from Mars.

This image was first published on 20 July 2017.

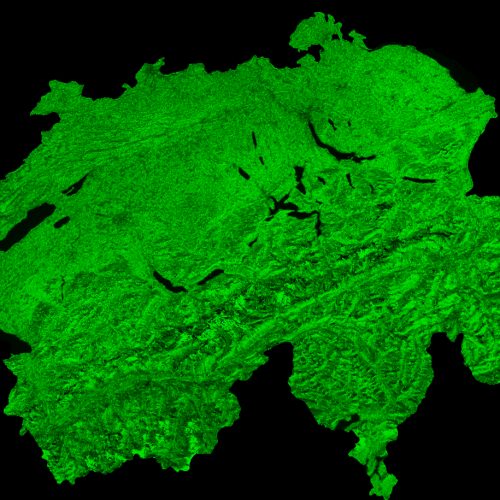

Switzerland by Proba-V

© ESA/Belspo – produced by VITO, Creative Commons

Launched on 7 May 2013, Proba-V is a miniaturised ESA satellite tasked with a full-scale mission: to map land cover and vegetation growth across the entire planet every two days.

This cloud-free image of Switzerland, acquired by Proba-V on 19 July 2015, has a 300 m per pixel resolution and is composed of cloud, shadow, and snow/ice screened observations over a period of 1 day.

Switzerland is one of ESA’s 22 member states.

Proba-V imagery at 1km resolution is owned by ESA, Proba-V imagery at 300m resolution is owned by Belspo, the Belgian Science Policy Office.

VITO Remote Sensing processes and distribute Proba-V data to users worldwide on behalf of ESA and Belspo.

This image is part of a set to celebrate the launch of ESA’s new Open Access (OA) policy for images, video and data: 22 freshly processed and thus new images of ESA’s 22 member states have just been released under the OA compliant Creative Commons CC-BY SA 3.0 IGO licence. The set consists of one cloud-free image in 300 m per pixel resolution of each ESA member state, i.e. Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

A meeting of minds

© NASA

A meeting of the minds aboard the International Space Station on 7 March 2015 with members of Expedition 42; astronauts US, Barry Wilmore (Commander) Top, Upside down, to the right cosmonaut Elena Serova, & ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti. Bottom centre US astronaut Terry Virts, top left cosmonauts Alexander Samokutyaev and Anton Shkaplerov.

Shooting star

© K. Miskotte, ESA

A bright fireball was spotted over the Netherlands and Belgium on 21 September at 21:00 CEST (19:00 GMT).

It was caused by a small meteoroid, estimated to be around several centimetres, entering Earth’s atmosphere and burning up.

The fireball was captured by a number of all-sky camera stations of the Dutch–Belgian meteor network operated by amateurs of the Dutch Meteor Society and the Meteor Section of the Royal Netherlands Association for Meteorology and Astronomy. They use automated photographic cameras with fish-eye lenses to capture images of the night sky on clear nights.

This remarkable image was captured by one of the stations, at Ermelo, operated by Koen Miskotte.

It is a 1.5 minute exposure with a Canon EOS 6D DSLR and a fish-eye lens.

The camera lens was equipped with an LCD shutter that, during the exposure, creates brief ‘breaks’ at a rate of 14 per second. These are the dark gaps in the trail making it look dashed. Because the LCD shutter rate is known, you can count the dashes and obtain the duration of the fireball: 5.3 seconds.

The image also provides information on the deceleration of the meteoroid in the atmosphere. In this case, it entered the atmosphere at 31 km/s and had slowed to 23 km/s by the time it disappeared (because it had burnt up completely) at 53 km altitude.

The bright star trail just below the tip of the fireball is Arcturus. The Big Dipper can be seen at right, above the treeline. The bright star near the centre of the image just left of the fireball trail is Vega.

Read full details on this brief but fiery event via Marco Langbroek’s SatTrackCam blog.

Austria

© ESA

The landlocked country of Austria, depicted in true colour by a mosaic of Envisat Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS) imagery.

Supersonic parachute testing

© ESA/ScienceOffice.org

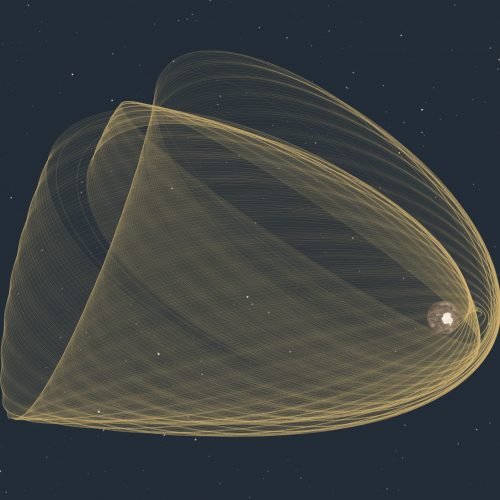

ESA’s Integral space observatory has been orbiting Earth for 15 years, observing the ever-changing, powerful and violent cosmos in gamma rays, X-rays and visible light. Studying stars exploding as supernovas, monster black holes and, more recently, even gamma-rays that were associated with gravitational waves, Integral continues to broaden our understanding of the high-energy Universe.

This image visualises the orbits of the spacecraft since its launch on 17 October 2002, until October of this year.

Integral travels in a highly eccentric orbit. Over time, the closest and furthest points have changed, as has the plane of the orbit. The orbit brought it to within 2756 km of Earth at its closest, on 25 October 2011, to 159 967 km at the furthest, two days later.

This kind of orbit provides long periods of uninterrupted observations with nearly constant background away from the radiation belts around Earth that would otherwise interfere with the satellite’s sensitive measurements.

In 2015, spacecraft operators conducted four thruster burns carefully designed to ensure that the satellite’s eventual entry into the atmosphere in 2029 will meet the Agency’s guidelines for minimising space debris. Making these disposal manoeuvres so early also minimises fuel usage, allowing ESA to exploit the satellite’s lifetime to the fullest.

The orbital changes introduced during these manoeuvres are seen in the wide-spaced orbits to the left of the image, highlighted in white in this annotated version of the image.

Watch a movie showing Integral’s orbits

Find out more about Integral in this infographic

Cloaked in red

© NASA, ESA, and D. Gouliermis (University of Heidelberg)

This stunning new Hubble image shows a small part of the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of the closest galaxies to our own. This collection of small baby stars, most weighing less than the Sun, form a young stellar cluster known as LH63. This cluster is still half-embedded in the cloud from which it was born, in a bright star-forming region known as the emission nebula LHA 120-N 51, or N51. This is just one of the hundreds of star-forming regions filled with young stars spread throughout the Large Magellanic Cloud.

The burning red intensity of the nebulae at the bottom of the picture illuminates wisps of gas and dark dust, each spanning many light-years. Moving up and across, bright stars become visible as sparse specks of light, giving the impression of pin-pricks in a cosmic cloak.

This patch of sky was the subject of observation by Hubble’s WFPC2 camera. Looking for and at low-mass stars can help us to understand how stars behave when they are in the early stages of formation, and can give us an idea of how the Sun might have looked billions of years ago.

A version of this image was submitted to the Hubble’s Hidden Treasures image processing competition by contestant Luca Limatola.

Supersonic parachute testing

© ESA/Vorticity

This parachute deployed at supersonic velocity from a test capsule hurtling down towards snow-covered northern Sweden from 679 km up, proving a crucial technology for future spacecraft landing systems.

Planetary landers or reentering spacecraft need to lose their speed rapidly to achieve safe landings, which is where parachutes come in. They have played a crucial role in the success of ESA missions such as ESA’s Atmospheric Entry Demonstrator, the Huygens lander on Saturn’s moon Titan and the Intermediate Experimental Vehicle spaceplane.

This 1.25-m diameter ‘Supersonic Parachute Experiment Ride on Maxus’, or Supermax, flew piggyback on ESA’s Maxus-9 sounding rocket on 7 April, detaching from the launcher after its solid-propellant motor burnt out.

After reaching its maximum 679 km altitude, the capsule began falling back under the pull of gravity. It fell at 12 times the speed of sound, undergoing intense aerodynamic heating, before air drag decelerated it to Mach 2 at an altitude of 19 km.

At this point the capsule’s parachute was deployed to stabilise it for a soft landing, and allowing its onboard instrumentation and camera footage to be recovered intact.

The experiment was undertaken by UK companies Vorticity Ltd and Fluid Gravity Engineering Ltd under ESA contract.

The data gathered by this test are being added to existing wind tunnel test campaigns of supersonic parachutes to validate newly developed software called the Parachute Engineering Tool (also developed by Vorticity), allowing mission designers to accurately assess the use of parachutes.

This development was supported through ESA’s General Support Technology Programme, which develops promising technologies for space. To find out more about ESA research and development projects, check our new Shaping the Future website.

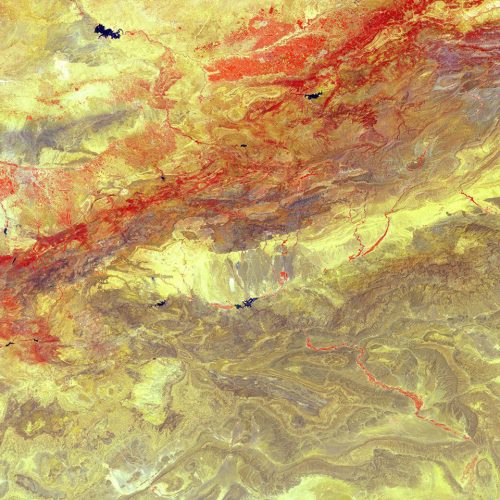

Proba-V images Atlas mountains

© ESA/Belspo – produced by VITO

North Africa’s High Atlas mountain range was imaged by ESA’s Proba-V minisatellite last summer, with vegetation shown in false-colour red.

The mountains – an extension of Europe’s Alpine system – stretch some 2400 km through Morocco, seen here, into Algeria and Tunisia. The Atlas mountains are actually a set of five ranges dividing the northern Mediterranean climate from the arid Sahara to the south.

A second, darker, range, the Anti-Atlas mountains, are seen to the south, with the the Draa River valley cutting through them – seen as a reddish line. The Draa, Morocco’s longest river, flows south from the city of Ouarzazate city into the Sahara.

The Berber-speaking Ouarzazate is a popular location for filmmakers, with productions such as Lawrence of Arabia (1962), The Mummy (1999) and Game of Thrones (2011–present) having been shot here.

Launched on 7 May 2013, Proba-V is a miniaturised ESA satellite tasked with a full-scale mission: to map land cover and vegetation growth across the entire planet every two days.

Its main camera’s continent-spanning 2250 km swath width collects light in the blue, red, near-infrared and mid-infrared wavebands at 300 m resolution and down to 100 m resolution in its central field of view.

VITO Remote Sensing in Belgium processes and then distributes Proba-V data to users worldwide. An online image gallery highlights some of the mission’s most striking images so far, including views of storms, fires and deforestation.

This 100-m resolution image was acquired on 13 July 2017.

Light continues to echo three years after stellar outburst

© NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/STScI)

The Hubble Space Telescope’s latest image of the star V838 Monocerotis (V838 Mon) reveals dramatic changes in the illumination of surrounding dusty cloud structures. The effect, called a light echo, has been unveiling never-before-seen dust patterns ever since the star suddenly brightened for several weeks in early 2002.

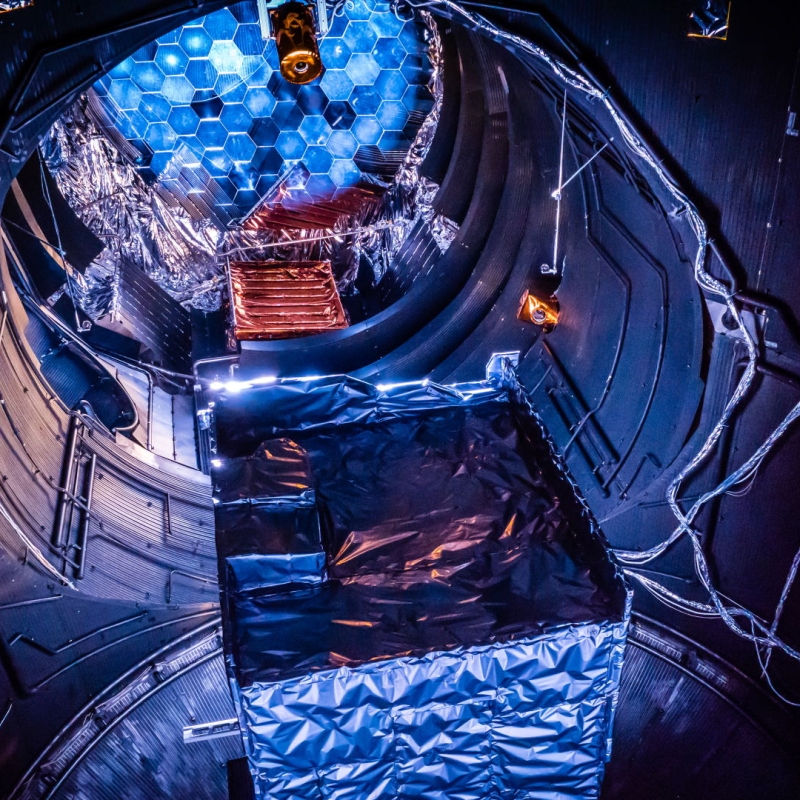

Mercury Transfer Module in space simulator

© ESA–C. Carreau

The BepiColombo Mercury Transfer Module has completed its final major test inside ESA’s Large Space Simulator, proving it will be able to withstand the temperature extremes it will experience on its journey to Mercury.

On the one hand, the mission will be exposed to the cold vacuum of space. On the other, it will travel close to the Sun, receiving 10 times the solar energy than we do on Earth. This translates to about 11 kW per sq m at Mercury, with the spacecraft expected to endure heating to about 350ºC, similar to a pizza oven.

Inside the simulator, the largest of its kind in Europe at 15m high and 10m wide, pumps create a vacuum a billion times lower than standard sea-level atmosphere, while the chamber’s walls are lined with tubes pumped with liquid nitrogen to create low temperatures of about –180ºC. At the same time, a set of 25kW IMAX projector-class lamps are used with mirrors to focus light onto the craft to generate the highest temperatures.

During the latest tests, carried out between 24 November and 4 December 2017, the module was rotated through 13º either side to monitor the heating and distribution. The ion engines were also activated – without creating thrust from an ion beam given the confines of the test chamber – to confirm that the module’s electric propulsion system can operate in this challenging environment

The module is seen here stacked on a replica interface to mimic the science orbiters that it will be attached to during launch and the 7.2 year journey to Mercury. The four ion thrusters are seen on the top of module in this orientation. Not present in this test, the module will also be equipped with two solar wings that will unfold to a span of 30 m.

The transfer module’s job is to carry ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and Japan’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter to the planet, where they will separate and enter their respective orbits. The craft will use a combination of gravity assist flybys at Earth, Venus and Mercury along with the transfer module’s ion thrusters to reach its destination.

The module will now be checked before the entire assembly is shipped to Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana next year. With this last major test complete, the mission is on track to be launched in the two-month window opening on 5 October 2018.

Technical details about the Large Space Simulator

More about BepiColombo’s high temperature challenge

Latest news and background info about BepiColombo

Cool sunrise

© ESA/NASA

ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet took this image from on board the International Space Station. He posted it on social media, commenting: “Flying into the sunrise is really cool. When the sun hits the Cupola windows, you can immediately feel its heat warming up the station.”

Thomas’ Proxima mission is the ninth long-duration mission for an ESA astronaut. It is named after the closest star to the Sun, continuing a tradition of naming missions with French astronauts after stars and constellations.

During Proxima, Thomas will perform around 50 scientific experiments for ESA and France’s space agency CNES as well as take part in many research activities for the other Station partners. The mission is part of ESA’s vision to use Earth-orbiting spacecraft as a place to live and work for the benefit of European society while using the experience to prepare for future voyages of exploration further into the Solar System.

LEGO astronaut flying in space

© ESA / NASA

Flying at a distance of 400 kilometers above Earth, Danish ESA astronaut Andreas Mogensen announced the winner of the iriss LEGO education competition.

The competition for Danish schoolchildren attracted wide interest. More than 200 teams of children aged 6-10 from schools all over Denmark built and filmed LEGO space stories on the iriss mission.

The competition is arranged in cooperation with ESA and the Danish House of Natural Sciences and is part of the project “Rumrejsen 2015” (Space Journey 2015), which is an educational initiative by the Danish National Centre for Science Education and the House of Natural Sciences. Learn more on the Danish website rumrejsen.dk (in Danish).

Aurora over Europe

© ESA/NASA

ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet took this photo of northern Europe from on board the International Space Station. An aurora can be seen to the north.

Thomas’ Proxima mission is the ninth long-duration mission for an ESA astronaut. It is named after the closest star to the Sun, continuing a tradition of naming missions with French astronauts after stars and constellations.

During Proxima, Thomas will have performed around 50 scientific experiments for ESA and France’s space agency CNES, as well as take part in many research activities for the other Station partners. The mission is part of ESA’s vision to use Earth-orbiting spacecraft as a place to live and work for the benefit of European society while using the experience to prepare for future voyages of exploration further into the Solar System.

Ariane 5 liftoff on flight VA233

© ESA–Stephane Corvaja, 2016

Liftoff of Ariane flight VA233, carrying four Galileo satellites, from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, on 17 November 2016.

Europe at night

© ESA/NASA

ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst took this image circling Earth on the International Space Station during his six-month Blue Dot mission.

Galileo lifts off

© ESA-Manuel Pedoussaut

Liftoff of Ariane 5 Flight VA240 from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana took place at 18:36 UTC (19:36 CET, 15:36 local time) on Tuesday 12 December 2017, carrying Galileo satellites 19–22.

Looking up from down under

© Dylan O’Donnell

ESA’s 35 m-diameter dish antenna at New Norcia, Western Australia, glows with reflected laser light in this photo, taken by Dylan O’Donnell, a photographer based in Byron Bay, New South Wales, Australia.

The deep-space tracking antenna provides critical communications with missions such as Rosetta, Mars Express and Gaia – all voyaging millions of kilometres away in the Solar System.

Next week, ESA will officially inaugurate a new, smaller 4.5-m satellite-tracking antenna recently built at the station (just a few hundred metres from the big dish). It can quickly and with high precision lock onto and track launch vehicles, such as Europe’s Ariane 5, Vega and Soyuz, and satellites during their critical initial orbits, up to roughly 100 000 km out.

The Agency has invited a group of social media followers to join us at the inauguration for a special, separate programme, including briefings on current and future planetary missions, deep-space communications, ground station engineering and next-generation lasers-in-space technology. Participants will also be guided on an exclusive, behind-the-scenes tour of the ground station facilities and antennas.

Participation in ESA’s social media events is free for selected attendees, but all must follow one of ESA’s social media channels and they cover their own travel and other costs.

Waving at Europe

© ESA / NASA

A picture of United Kingdom under aurora taken by ESA astronaut Tim Peake during his six-month Principia on the International Space Station.

He is performing more than 30 scientific experiments for ESA and taking part in numerous others from ESA’s international partners.

More about the Principia mission: http://www.esa.int/principia

More photos from Tim on his flickr photostream: https://www.flickr.com/photos/timpeake

Concordia runway

© ESA/IPEV/PNRA – A. Salam

Concordia research station in Antarctica is a place of extremes. In winter, no sunlight is seen for four months and the typical crew of 12 live in complete isolation. In summer, the Sun stays above the horizon and over 60 scientists arrive at the base.

During ‘summer camp’, aircraft take off on an almost daily basis. Concordia becomes a hubbub of activity as researchers from disciplines as diverse as astronomy, seismology, human physiology and glaciology descend to study in this unique location.

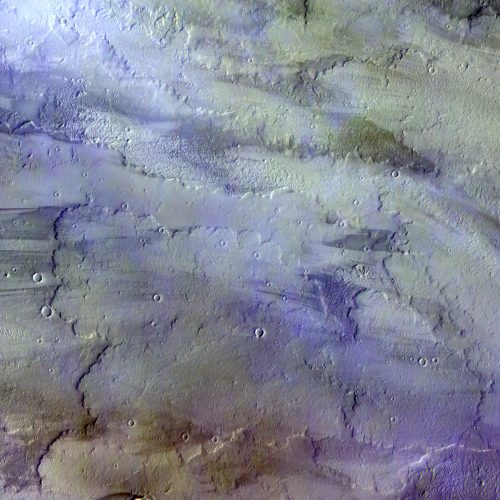

Clouds over lava flows on Mars

© ESA/Roscosmos/CaSSIS

Diffuse, water-ice clouds, a hazy sky and a light breeze. Such might have read a weather forecast for the Tharsis volcanic region on Mars on 22 November 2016, when this image was taken by the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter.

Clouds, most likely of water-ice, and atmospheric haze in the sky are coloured blue/white in this image.

Below, 630 km west of the volcano Arsia Mons, the southernmost of the Tharsis volcanoes, outlines of ancient lava flows dominate the surface. The dark streaks are due to the action of wind on the dark-coloured basaltic sands, while redder patches are wind blown dust. A handful of small impact craters can also be seen.

The Trace Gas Orbiter, a joint effort between ESA and Roscosmos, arrived at Mars on 19 October last year. Since March it has been repeatedly surfing in and out of the atmosphere, generating a tiny amount of drag that will steadily pull it into a near-circular 400 km altitude orbit. It is expected to begin its full science operational phase from this orbit in early 2018.

Prior to this ‘aerobraking’ phase, several test periods were assigned to check the four science instrument suites from orbit and to refine data processing and calibration techniques.

The false-colour composite shown here was made from images taken with the Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System, CaSSIS, in the near-infrared, red and blue channels.

The image is centred at 131°W / 8.5°S. The ground resolution is 20.35 m/pixel, and the image is about 58 km across. At the time the image was taken, the altitude was 1791 km, yielding a ground track speed of 1.953 km/s.

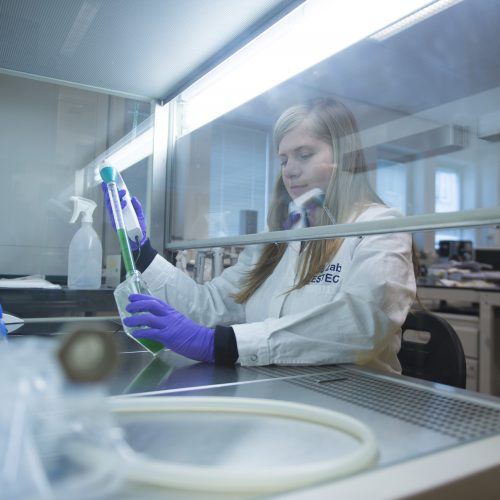

Young graduate trainee Justyna Barys

© ESA–G. Porter

Justyna Barys, a graduate trainee working in ESA’s technical centre, has been selected as one of the 30 Under 30 – Europe Industry List compiled by leading business publisher Forbes.

Justyna, 26, has been working in ESA’s Life and Physical Sciences Instrumentation section in its Netherlands-based technical heart since October 2015, focusing on the MELiSSA Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative project to develop closed-loop life support for future deep-space expeditions.

She joins a diverse range of millennial European entrepreneurs, engineers and designers – the final Forbes selection having been made by an all-star jury that included Stéphane Israël, CEO of Arianespace.

Justyna specialised in biotechnology at the Lodz University of Technology before coming to ESA: “I’d always been interested in astronomy and space, so would regularly visit the NASA and ESA websites.

“I didn’t think the Young Graduate Trainee vacancy was something for me at first, but it turned out to be very interesting in terms of my interests and the combination of engineering and microbiology in my background.”

Justyna’s work focuses on nitrogen-converting bacteria, a crucial element in the various processes making up MELiSSA: “We are used to provision of oxygen, water and food by Earth’s ecosystem. It would be ideal to carry Earth’s ecosystem with us for exploring the Solar System. Unfortunately, mass and volume do not allow it.

“Instead, the MELiSSA approach is inspired by the principle of a closed ’aquatic’ lake ecosystem. The carbon dioxide and waste products are progressively processed to allow the culture of plants and algae. These plants and algae will then provide food, oxygen and water purification.

“To grow plants we need nitrogen. Human urine is a good source of nitrogen, but doesn’t contain it in the form that plants need – nitrates. But there are bacteria, originally taken from soil, that perform this conversion job, so I’ve been attempting to cultivate them and study how they grow.

“To begin with I was experimenting with small flasks, using polyvinyl acetate beads to promote the growth of biofilm which makes this kind of bacteria more active.

“As a next step I’ve been building a bioreactor for continuous culture. Once it is finished, nutrients and oxygen will be supplied, pH controlled and effluent removed to promote their continuous growth and monitor their conversion rate of ammonia into nitrates.”

The research is only one element of the 11-nation MELiSSA effort, including the full-scale pilot plant in Spain’s University Autònoma of Barcelona.

Justyna has also worked on another aspect of MELiSSA, preparing an experiment on highly nutritious oxygen-producing Spirulina bacteria for a teacher workshop.

Set to leave ESA in September, Justyna is looking for a PhD position in microbiology, biotechnology or environmental engineering.

Alps from Space

© ESA / NASA

ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst sent this image of the Western Alps from the International Space Station with the text: “The majestic Alps. Where two continents colide.”

The image shows France, Switzerland and Italy, including the hometown of ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti Malè in the Italian province of Trento. Samantha will take over from Alexander on the weightless research centre, launching with NASA astronaut Terry Virts and Anton Shkaplerov on her Futura mission two weeks after Alexander returns to Earth.

Working 400 km above our planet, Alexander is taking beautiful pictures in his spare time. Follow his Blue Dot mission via alexandergerst.esa.int

Measuring powder flow

© STFC–S. Kill

The ESA–RAL Advanced Manufacturing Laboratory on Harwell Campus, UK, assesses new material processes, joining techniques and 3D printing technologies for application in space.

One of its tasks is to measure the characteristics of special powders used in 3D printing. The lab puts each sample through various experiments designed to record the material’s apparent and tap density, flowability, powder size distribution and morphology.

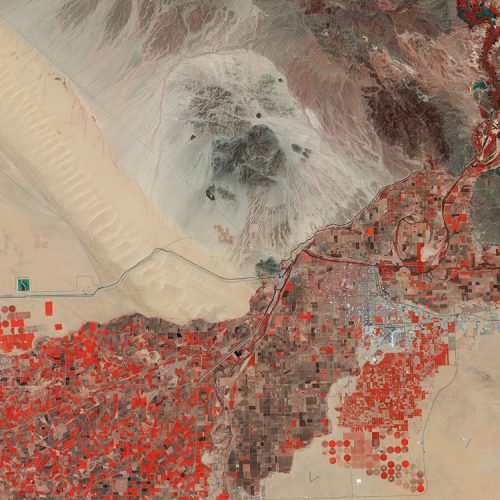

Yuma chequerboard

© Copernicus Sentinel data (2015)/ESA

This false-colour Sentinel-2A image captured on 20 August 2015 takes us to the city of Yuma in the United States, in southwestern Arizona.

Visible in the image in scattered greys, Yuma is home to some 90 000 people. Situated along the Colorado River, the Mexican frontier lies just west of it and California lies to the north.

The fence forming the border is visible as a fine and perfectly straight line, running from left to right through the image between the irrigation canal and the irrigated fields west of the city. Just north of the canal, a small square marks a water reservoir for irrigating the fields in this highly arid region.

Founded in 1854, Yuma is the centre of large irrigation districts that converted parts of the desert into rich farmland.

It is considered to be the winter vegetable capital of the US because it has some of the most fertile soil in the country, stemming from sediments deposited by the Colorado River over thousands of years. These lay the foundation for making it the third most productive in the entire US for vegetables. It is also known for wheat – two thirds is exported, mainly to Italy for producing premium pasta.

The false-colour bands render the farmed fields in varying shades of browns and red. The circular features are created by centre-pivot irrigation, while rectangular fields use different irrigation methods that deliver the water along straight lines. The shades of red indicate how sensitive the multispectral instrument on Sentinel-2A is to differences in chlorophyll content, providing key information on vegetation health.

Also visible in the image are the Yuma International Airport just south of town, and parts of the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge to the east, which protects the desert bighorn sheep, while offering hiking and camping in the rugged wilderness.

Sentinel-2A has been in orbit since 23 June 2015 as a polar-orbiting, high-resolution satellite for land monitoring, providing imagery of vegetation, soil and water cover, inland waterways and coastal areas.

This image is also featured on the Earth from Space video programme.

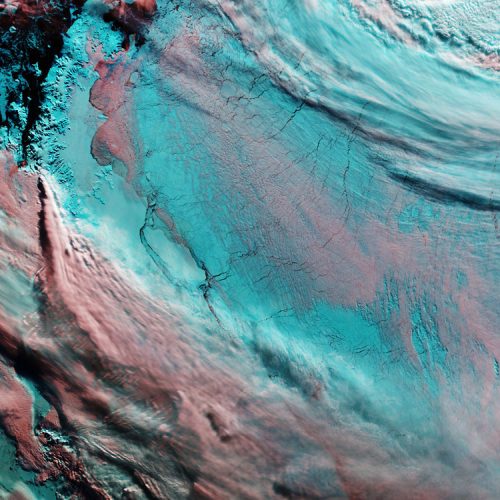

Larsen Ice Shelf

© contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017), processed by ESA

The Copernicus Sentinel-3A satellite takes us over the Antarctic Peninsula and the adjacent Larsen Ice Shelf, from which a massive iceberg broke off in July.

The image has been manipulated, so clouds appear pink while snow and ice are blue to help us differentiate between them. The only land clearly visible is the tip of the Peninsula in the upper left, while sea ice covers the Weddell Sea to the right.

Captured on 25 September, the image shows the iceberg near the centre. The A68 berg had been jostling back and forth against the ice shelf, but more recent satellite imagery revealed that the gap between the berg and the shelf is widening – possibly drifting out to sea.

An iceberg’s progress is difficult to predict. It may remain in the area for decades, but if it breaks up, parts may drift north into warmer waters. Since the ice shelf is already floating, this giant iceberg does not influence sea level.

A68 is about twice the size of Luxembourg and with its calving has changed the outline of the Antarctic Peninsula forever – about 10% of the area of the Larsen C Ice Shelf has been removed.

The loss of such a large piece is of interest because ice shelves along the peninsula play an important role in ‘buttressing’ glaciers that feed ice seawards, effectively slowing their flow.

Previous events further north on the Larsen A and B shelves, captured by ESA’s ERS and Envisat satellites, indicate the flow of glaciers behind can accelerate when a large portion of an ice shelf is lost, contributing to sea-level rise.

This image is featured on the Earth from Space video programme.

Sentinel-5P liftoff

© ESA–Stephane Corvaja, 2017

The atmosphere-monitoring satellite for Europe’s Copernicus programme, Sentinel-5P, lifted off on a Rockot from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northern Russia at 09:27 GMT (11:27 CEST) on 13 October 2017.

Sentinel-5P – also known as Sentinel-5 Precursor – is the first Copernicus mission dedicated to monitoring our atmosphere. The satellite carries the state-of-the-art Tropomi instrument to map a multitude of trace gases such as nitrogen dioxide, ozone, formaldehyde, sulphur dioxide, methane, carbon monoxide and aerosols – all of which affect the air we breathe and therefore our health, and our climate.

With a swath width of 2600 km, it will map the entire planet every day. Information from this new mission will be used through the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service for air quality forecasts and for decision-making.

The mission will also contribute to services such as volcanic ash monitoring for aviation safety and for services that warn of high levels of UV radiation, which can cause skin damage.

In addition, scientists will also use the data to improve our knowledge of important processes in the atmosphere related to the climate and to the formation of holes in the ozone layer.

Sentinel-5P was developed to reduce data gaps between the Envisat satellite – in particular the Sciamachy instrument – and the launch of Sentinel-5, and to complement GOME-2 on MetOp.

In the future, both the geostationary Sentinel-4 and polar-orbiting Sentinel-5 missions will monitor the composition of the atmosphere for Copernicus Atmosphere Services. Both missions will be carried on meteorological satellites operated by Eumetsat.

Until then, the Sentinel-5P mission will play a key role in monitoring and tracking air pollution.

Sentinel-5P is the result of close collaboration between ESA, the European Commission, the Netherlands Space Office, industry, data users and scientists. The mission has been designed and built by a consortium of 30 companies led by Airbus Defence and Space UK and NL.

Deep Blue Read Sea Reefs

© Copernicus Sentinel data (2015)/ESA

This beautiful true-colour image features the Red Sea coral reefs off the coast of Saudi Arabia.

This vast, desolate area in the very northern corner of the Red Sea is bordered by the Hejaz Mountains to the east. The area was once criss-crossed by ancient trade routes that played a vital role in the development of many of the region’s greatest civilisations.

Today, the Red Sea separates the coasts of Egypt, Sudan and Eritrea to the west from those of Saudi Arabia and Yemen to the east.

It contains some of the world’s warmest and saltiest seawater. With hot sunny days and the lack of any significant rainfall, dust storms from the surrounding deserts frequently sweep across the sea. This hot dry climate causes high levels of evaporation from the sea, which leads to the Red Sea’s high salinity.

It is just over 300 km across at its widest point, about 1900 km long and up to 2600 m deep. Much of the immediate shoreline is quite shallow, dotted with coral reefs along most of the coast – making excellent diving spots in many areas.

Its name derives from the colour changes in the waters. Normally, the Red Sea is an intense blue–green. Occasionally, however, extensive algae blooms form and when they die off they turn the sea a reddish-brown colour.

The Red Sea lies in a fault separating two blocks of Earth’s crust – the Arabian and African plates.

Navigation in the Red Sea is difficult. The shorelines in the northern half provide some natural harbours, but the growth of coral reefs has restricted navigable channels and blocked some harbour facilities.

Shallow submarine shelves and extensive fringing reef systems rim most of the Red Sea, by far the dominant reef type found here.

The lighter blue water depicted in the image means that the water is shallower than the surrounding darker blue water.

Furthermore, water clarity is exceptional in the Red Sea because of the lack of river discharge and low rainfall. Therefore, fine sediment that typically plagues other tropical oceans, particularly after large storms, does not affect the Red Sea reefs.

Also featured on the Earth from Space video programme, this image was captured by Sentinel-2A on 28 June 2015 after its instruments had been activated.

ISS with ATV & Shuttle docked

© ESA/NASA/Roscosmos

This image of the International Space Station, the docked ATV-2 Johannes Kepler and the docked Space Shuttle Endeavour, flying at an altitude of approximately 220 miles, was taken by ESA astronaut and Expedition 27 crew member Paolo Nespoli from the Soyuz TMA-20 following its undocking on 23 May 2011 (USA time). They are the first-ever images of a space shuttle docked to the International Space Station. Onboard the Soyuz were Russian cosmonaut and Expedition 27 commander Dmitry Kondratyev; Nespoli; and NASA astronaut Cady Coleman. Coleman and Nespoli were both flight engineers. The three landed in Kazakhstan later that day, completing 159 days in space.

More images here.

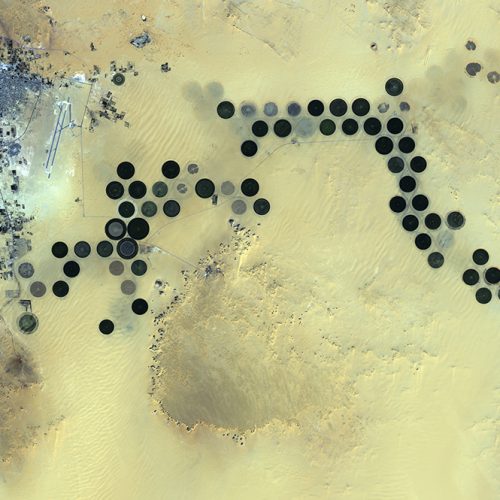

Libya’s Al Jawf oasis

© JAXA, ESA

Deep in the Sahara Desert, the Al Jawf oasis in southeastern Libya is pictured in this image from Japan’s ALOS satellite. The city can be seen in the upper left corner, while large, irrigated agricultural plots appear like Braille across the image. Between the city and the plots we can see the two parallel runways of the Kufra Airport. The agricultural plots reach up to a kilometre in diameter. Their circular shapes were created by a central-pivot irrigation system, where a long water pipe rotates around a well at the centre of each plot. Since the area receives virtually no rainfall, fossil water is pumped from deep underground for irrigation.

Japan’s Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS) captured this image on 24 January 2011 with its Advanced Visible and Near Infrared Radiometer type-2, which charts land cover and vegetation in the visible and near-infrared spectral bands at a resolution of 10 m. ESA supports ALOS as a Third Party Mission, which means ESA uses its multimission ground systems to acquire, process, distribute and archive data from the satellite to its user community.

This image is featured on the Earth from Space video programme.

Comet in May 2015

© ESA/Rosetta/NavCam

Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in May 2015, the same month that Rosetta also made the first detection of the organohalogen methyl chloride, CH3CL with its ROSINA instrument.

In May 2015 Rosetta was between 1.7 and 1.5 astronomical units from the Sun, just outside the orbit of Mars. Its closest approach to the Sun, 1.2 AU, was reached three months later, in August. The increasing heat warmed the ices on the comet’s surface and released gas, dragging dust out with it to create the comet’s fuzzy atmosphere.

This single frame navigation camera image was taken on 23 May 2015 from a distance of 138.1 km from the comet centre. The image has a resolution of 11.8 m/pixel and measures 12.1 km across.

Pacific Ocean from Space

© NASA / ISS

Astronaut walking on the moon

© NASA

John Young took this pan on the far side of Plum Crater from the Rover on the Apollo 16 mission with Charlie Duke in the front.

Landing of the Soyuz TMA-19M spacecraft

© SA–Stephane Corvaja, 2016

ESA astronaut Tim Peake, NASA astronaut Tim Kopra and commander Yuri Malenchenko landed in the steppe of Kazakhstan on Saturday, 18 June in their Soyuz TMA-19M spacecraft. The trio spent 186 days on the International Space Station.

The landing brings Tim Peake’s Principia mission to an end but the research continues. Tim is the eighth ESA astronaut to complete a long-duration mission in space. He is the third after Alexander Gerst and Andreas Mogensen to fly directly to ESA’s astronaut home base in Cologne, Germany, for medical checks and for researchers to collect more data on how Tim’s body and mind have adapted to living in space.

Section of Hubble solar wing

© ESA–G. Porter

A deceptively valuable wall hanging: this section of the NASA–ESA Hubble Space Telescope’s solar array flew for eight years in space before being returned to Earth aboard a Space Shuttle, and is now displayed at ESA’s technical centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands.

See it for yourself at ESA’s Open Day in the Netherlands on Sunday 8 October. The theme this year is Bringing Space to Earth, focussing on knowledge, hardware and people returned to the ground from space.

VIP guests for the Open Day have been confirmed: astronauts Michael Foale of the UK, Dumitru Prunariu of Romania, Ulf Merbold and Ernst Messerschmid of Germany, Dirk Frimout of Belgium, Jean-Jacques Favier and Claudie Haigneré of France and André Kuipers of the Netherlands.

More than 9200 people have registered to attend the event.

Forty years ago this year NASA and ESA agreed to be partners on the Hubble Space Telescope, which was launched into orbit on 24 April 1990.

ESA provided the first two generations of solar wings for Hubble, replaced and returned during later servicing missions. ESA’s solar power engineers had the valuable opportunity to study how solar arrays degraded in the space environment.

Today, Hubble is powered by US-made solar wings, but they are kept trained on the Sun by the original European drive mechanisms.

Glacier ice

© Simon Steinberger, Pixabay

Ice Glacier Frozen

Living Planet Symposium 2022

© ESA

ESA’s Living Planet Symposium 2022 was held at the World Conference Center in Bonn, Germany, on 23–27 May. The Living Planet Symposia bring together scientists and researchers from all over the world to present and discuss the latest findings on Earth science and advances in Earth observation technologies. Moreover, these extraordinary events also offer unique forums for decision-makers to be better equipped with information, for partnerships to be forged and formalised, for space industries to join the conversation, for students to learn, and for all to explore the concepts of New Space such as the digital transformation and commercialisation.

The Living Planet Symposium 2022, which was organised with the support of the German Aerospace Center DLR, has been all of this and more.

Constructing the Space Station

© NASA

NASA astronaut Robert Curbeam works on the International Space Station’s S1 truss during the space shuttle Discovery’s STS-116 mission in Dec. 2006. European Space Agency astronaut Christer Fuglesang (out of frame) was his partner in the 6-hour, 36-minute spacewalk.

During Discovery’s mission to the station, the STS-116 crew continued construction of the orbital outpost, adding the P5 spacer truss segment during the first of four spacewalks. The next two spacewalks rewired the station’s power system, preparing it to support the station’s final configuration and the arrival of additional science modules. A fourth spacewalk was added to allow the crew to retract solar arrays that had folded improperly.

Fuorcla Surlej milky way

© Lukas Schlagenhauf, Flickr

There’s a lake at the Fuorlca Surlej which would offer a nice reflexion of the Piz Roseg, its glacier, and the Milky Way. The emphasis here is on “would”, two weeks before the photo the lake was still covered with snow and thus Lukas had to change plans and went for a full panorama shot instead.

The night sky in the Engadin valley is supposed to be one of the darkest in Switzerland, but on that particular night a certain glow remained in the sky, therefore the contrast in the Milky Way is not as strong as Lukas was hoping for.

Testing ESA's Jupiter mission

© ESA–M.Cowan

The JUICE Thermal Development Model (TDM) inside the Large Space Simulator (LSS) at ESA’s European Space Research & Technology Centre (ESTEC) during a May 2018 test campaign for ESA’s Jupiter mission.

Eagle Nebula M16

© NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

This image of the Eagle Nebula, M16, was taken in November 2004 with the Advanced Camera for Surveys aboard the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

It shows a billowing tower of cold gas and dust, 9.5 light-years high, rising from a stellar nursery. Stars in the Eagle Nebula are born in these clouds of cold hydrogen gas, and the tower may be a giant ‘incubator”for those newborn stars.

Pilars of Creation

© NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

Eagle Nebula M16

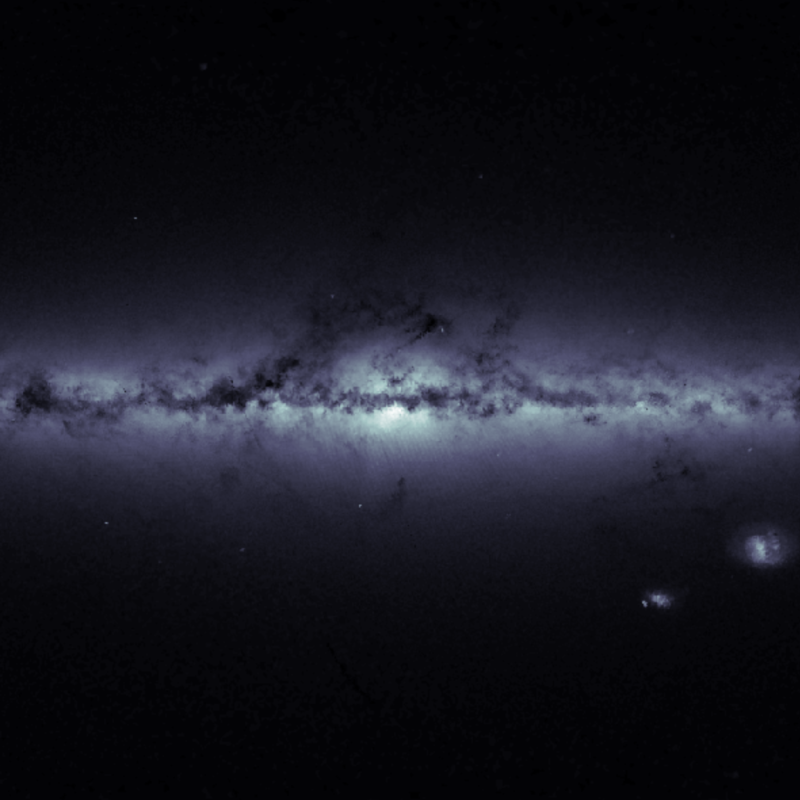

© ESA/Gaia, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

The outline of our Galaxy, the Milky Way, and of its neighbouring Magellanic Clouds, in an image based on housekeeping data from ESA’s Gaia satellite, indicating the total number of stars detected every second in each of the satellite’s fields of view.

Brighter regions indicate higher concentrations of stars, while darker regions correspond to patches of the sky where fewer stars are observed.

The plane of the Milky Way, where most of the Galaxy’s stars reside, is evidently the brightest portion of this image, running horizontally and especially bright at the centre. Darker regions across this broad strip of stars, known as the Galactic Plane, correspond to dense, interstellar clouds of gas and dust that absorb starlight along the line of sight.

The Galactic Plane is the projection on the sky of the Galactic disc, a flattened structure with a diameter of about 100 000 light-years and a vertical height of only 1000 light-years.

Beyond the plane, only a few objects are visible, most notably the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, two dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way, which stand out in the lower right part of the image. A few globular clusters – large assemblies up to millions of stars held together by their mutual gravity – are also sprinkled around the Galactic Plane.

Acknowledgement: this image was prepared by Edmund Serpell, a Gaia Operations Engineer working in the Mission Operations Centre at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO) licence.